Singleton

© Ioannis Kostaras

| Name | Singleton |

|---|---|

| Scope | Object |

| Purpose | Creational |

| Intent | Ensure that a class has only one instance and provide a global point of access to it. |

| Also Known As | |

| Motivation | It is necessary for some classes to have only one instance; e.g., to hold system-wide state information or manage a resource (e.g. a database) |

| Applicability | when there must be exactly one instance of a class, and it must be accessible from a well-known point of access |

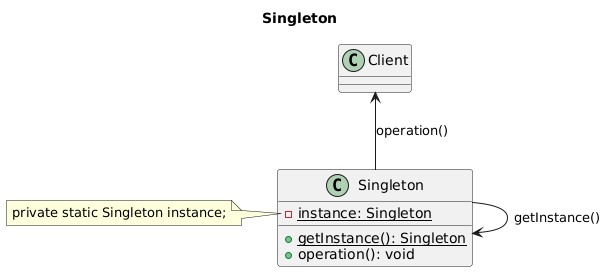

| Structure |  |

| Participants | A Singleton class defines a static member function that returns a pointer to the sole instance of the class. This Instance() function creates the instance if it does not already exist |

| Collaborations | Clients access the sole instance solely through this function |

Implementation

- static instance operation

- registering the singleton instance

Java

Let’s start with the simplest implementation. How can we guarantee a single instance?

public final class Singleton {

public static final Singleton INSTANCE = new Singleton();

// private empty constructor

private Singleton() {

// initialize any state here

}

// ...

}

public class Client {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Constructor is private -- cannot use new

Singleton s1 = Singleton.INSTANCE;

Singleton s2 = Singleton.INSTANCE;

if ( s1 == s2 )

System.out.println( "Same instance" );

}

}

A static class is one of the approaches that makes a class “Singleton”, since static means shared by all objects of the class. There should be no other way to construct an object apart from the one provided by the class. To achieve that:

- make all constructors

private, and create at least one constructor to prevent the compiler from synthesizing a default constructor for you (which it will create using package access); finalprevents cloneability from being added through inheritance. SinceSingletonis inherited directly fromObject, theclone()method remainsprotectedso it cannot be used (doing so produces a compile-time error). However, if you’re inheriting from a class hierarchy that has already overriddenclone()aspublicand implementedCloneable, the way to prevent cloning is to overrideclone()and throw aCloneNotSupportedException.

This implementation is also thread safe, since static final guarantees that the object will be created.

A similar way is to use a factory method to provide the single point of access:

// Singleton using a factory method

public final class Singleton {

private static final Singleton INSTANCE = new Singleton();

// private empty constructor

private Singleton() {

// initialize any state here

}

public static Singleton getInstance() {

return INSTANCE;

}

}

Lazy initialisation is useful for expensive objects (by lazy initialisation we mean initialise the object only when needed, i.e. when the Singleton class is being called for the first time):

// Singleton with lazy initialization

public final class Singleton {

private static Singleton singleton = null;

// private constructor

private Singleton() {

// initialize any state here

}

public static Singleton getInstance() {

if (singleton == null)

singleton = new Singleton();

return singleton;

}

}

public class Client {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Constructor is private -- cannot use new

Singleton s1 = Singleton.getInstance();

Singleton s2 = Singleton.getInstance();

if ( s1 == s2 )

System.out.println( "Same instance" );

}

}

However, the above implementation is not thread-safe. To make it thread-safe:

// Thread-safe singleton with lazy initialization

public final class Singleton {

private volatile static Singleton singleton = null;

private static final Object classLock = Singleton.class;

// private constructor

private Singleton() {

// initialize any state here

}

public static Singleton getInstance() {

if (singleton == null)

synchronized (classLock) {

if (singleton == null)

singleton = new Singleton();

return singleton;

}

}

}

Double-checked locking in Java is considered correct and safe under the Java Memory Model (JMM) only if the shared field (the singleton instance) is declared volatile and all object construction is complete before publishing the reference.

Without volatile, the object construction and the assignment to the reference can be reordered, leading to another thread seeing a partially-initialized object. Declaring the singleton reference as volatile prevents this reordering and ensures visibility of the fully constructed object to all threads.

Note: Double check locking doesn’t work in JVM 1.4 or earlier (in case you ‘re still working with such old versions).

All initialization must be done before assigning the reference to instance, to avoid leaking a partially-constructed object.

As a refresher, when you are using a synchronized marker, you have two choices on its granularity: “method locks” or “block locks”. If you put the synchronized on a method, you are locking on this object implicitly.

An effective lazy initialisation can be provided by using a Holder class:

// Singleton that uses a Holder class

public final class Singleton {

private static class SingletonHolder {

static final Singleton INSTANCE = new Singleton();

private SingletonHolder() {}

}

// private constructor

private Singleton() {

// initialize any state here

}

public static Singleton getInstance() {

return SingletonHolder.INSTANCE;

}

}

The class loader guarantees that the class is correctly initialised.

If you need a Singleton that can be serialized:

public final class Singleton implements Serializable {

public static final Singleton INSTANCE = new Singleton();

// private empty constructor

private Singleton() {

// initialize any state here

}

// readResolve method to preserve singleton property

private Object readResolve() {

// Return the instance and let the garbage collector

// take care of the rest.

return INSTANCE;

}

}

If you don’t implement readResolve(), then on the other side, a new Singleton object will be created.

Since Java 5.0 you can use enums:

// Singleton using enum

public enum Singleton {

INSTANCE;

}

- It can be serialized, but serialization makes no sense, and its fields cannot be serialized neither

- Client code can only access fields

- It cannot be subclassed

But if the constructor(s) are private, how can we pass arguments to a Singleton?

C#

// Singleton pattern -- Lazy initialization

using System;

// "Singleton"

class Singleton {

// Fields

private static Singleton instance;

// Constructor

protected Singleton() {}

// Methods

public static Singleton Instance() {

// Uses "Lazy initialization"

if ( instance == null ) {

instance = new Singleton();

return instance;

}

}

}

Client code test:

/// <summary>

/// Client test

/// </summary>

public class Client

{

public static void Main()

{

// Constructor is protected -- cannot use new

Singleton s1 = Singleton.Instance();

Singleton s2 = Singleton.Instance();

if ( s1 == s2 )

Console.WriteLine( "The same instance" );

}

}

Below is a thread-safe Singleton implementation:

// Singleton pattern – Thread safe - Lazy initialization

using System;

// "Singleton"

class Singleton

{

// Fields

private static volatile Singleton? instance = null;

// Lock synchronization object

private static object syncLock = new object();

// Constructor

private Singleton() {}

// Methods

public static Singleton Instance()

{

// Support multithreaded applications through

// "Double checked locking" pattern which (once

// the instance exists) avoids

// locking every time the method is invoked

if (instance == null)

{

lock (syncLock)

{

if (instance == null)

{

instance = new Singleton();

}

}

}

return instance;

}

}

C++

// Singleton.h

class Singleton {

public:

static Singleton* Instance();

private:

static Singleton* pInstance;

Singleton();

};

// Singleton.cpp

#include "Singleton.h"

Singleton* Singleton::Instance()

{

if (pInstance == nullptr)

{

pInstance = new Singleton;

}

return pInstance;

}

Singleton* Singleton::pInstance = nullptr;

//

Rust

Known Uses

Java

C++

C#

Rust

## Known Uses ### Java

Runtime.getRuntime()uses the public constant implementationjava.awt.Toolkit.getDefaultToolkit()is a polymorphic Singleton; it creates an instance of the toolkit dynamically depending on the platform, e.g. Windows, Mac, Motif etc.

C#

C++

// Singleton.h

class Singleton {

public:

static Singleton* Instance();

// Prevent copy

Singleton(const Singleton&) = delete;

Singleton& operator=(const Singleton&) = delete;

private:

static Singleton* pInstance;

Singleton() {};

};

// Singleton.cpp

#include "Singleton.h"

Singleton* Singleton::Instance()

{

if (pInstance == nullptr)

{

pInstance = new Singleton;

}

return pInstance;

}

// Static member initialization

Singleton* Singleton::pInstance = nullptr;

// Client.cpp

#include "Singleton.h"

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

Singleton* singleton1 = Singleton::Instance();

Singleton* singleton2 = Singleton::Instance();

if (singleton1 == singleton2)

cout << "Same instances.";

else

cout << "Different instances.";

}

Rust

## Consequences ### Pros

- reduces namespace pollution

- makes it easy to change your mind and allow more than one instance (see ObjectPool)

Cons

- same drawbacks of a global variable if misused

- implementation may be less efficient than a global variable

- concurrency pitfalls

- Singletons are difficult to unit test because it’s impossible to substitute a mock implementation for a singleton unless it implements an interface that serves as its type.

Related Patterns

- Abstract factory, which is often used to return unique objects.

- Builder, which is used to construct a complex object, whereas a singleton is used to create a globally accessible object.

- Prototype, which is used to copy an object, or create an object from its prototype, whereas a singleton is used to ensure that only one prototype is guaranteed.

- Object Pool, which returns not a single instance but a limited number of instances of a class

Comparison of Singleton to a class of static methods

Why use Singleton when one could just create a final class and declare all its methods as static?

public final class StaticClass {

public static String getMethodA() {}

public static int getMethodB() {}

// ...

}

A global variable makes an object accessible, but has drawbacks

- Unwieldy: What should it be called? Where should it be declared?

- Unreliable: It does not prevent the declaration of other instances

Bibliography and further reading

- Bloch J. (2018), Effective Java, 3nd Edition, Addison-Wesley.

- Geary, D. (2003), Simply Singleton, JavaWorld.com.

- Eckel, B. (2003), Thinking in Patterns with Java, MindView.

- Freeman, E. & Freeman, E. (2021), Head First Design Patterns, 2nd Ed., O’ Reilly.

- GoF (1995), Design Patterns – Elements of reusable components, Addison-Wesley.

- JavaCamp, http://javacamp.org/designPattern/index.html, Singleton

- Kabutz, H. (2002), Double-checked locking, The Java Specialists’ Newsletter, Issue 061.

- Kabutz, H. (2002), J2EE Singleton, The Java Specialists’ Newsletter, Issue 052.

- Metsker, S. J. (2002), Design Patterns Java Workbook, Addison-Wesley.